In case you haven’t noticed, it is no longer your great grandfather’s healthcare system. In fact, your great grandfather did not have a healthcare system at all. Your great grandfather barely had a doctor, let alone an entire system.

In 1930, my father was pinned between the coal truck he was unloading and the house’s foundation. The vehicle’s rear bumper snagged his hip cracking his pelvis above the ball joint. After freeing himself from the clutches of the coal truck, and with the help of a passerby, he made his way home.

Did he call and ambulance, no. Did he go to the emergency clinic, no. Did he call or visit a doctor, no. Did he get a CAT scan, an MRI, an x-ray, an ultrasound, a blood test, or a psychiatric review to insure he was properly medicated for PTSD – no. What did he do? He went home to seek the skill and ministrations of his eldest sister who was standing in for his recently deceased mother.

Aside from the demonstration of the very real tenaciousness and innate self-reliance of our ancestors, what’s the point of his story? Simply this: 50 years ago, 100 years ago medical assistance was not an ordinary event. Suffice it to say that in the early part of the 20th century an individual saw a doctor less than once a year and expected to be in a hospital once or twice in his lifetime. In 1850 to 2017, using anecdotal evidence, an individual’s use of formalized medical care has soared from one or two events every ten years to dozens of events per year, a 100-fold increase.

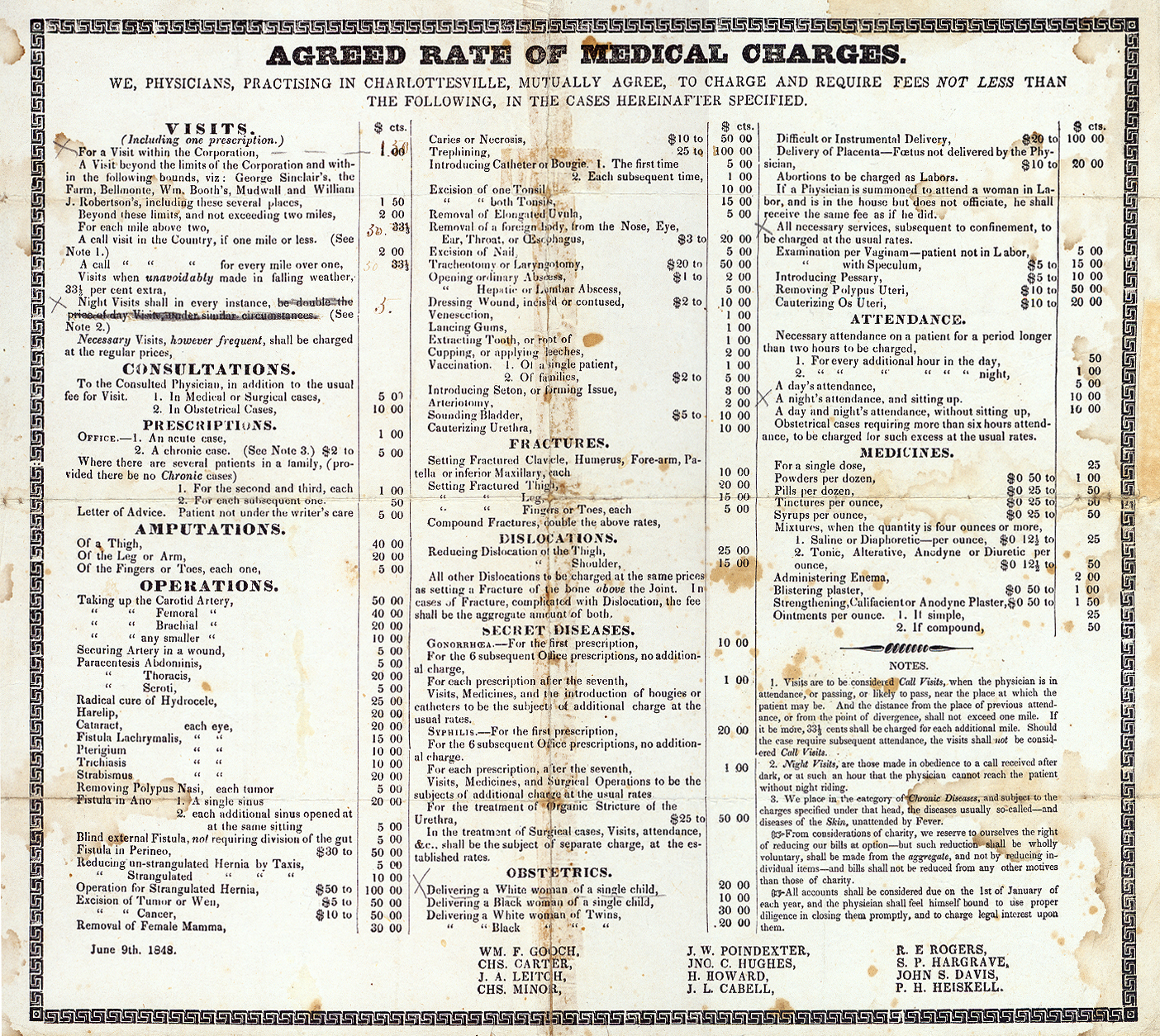

This increase is driven by the explosive advance of medical technology. In 1848, a published schedule of doctor’s fees contained some 45 procedures including medications. Today, the modern version of the simple illustration below is the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). Today’s HCPCS contains millions of procedures, in fact, the latest HCPCS contains 6000 categories, let alone specific procedures. In 150 years, the number of health-related products available to an individual has grown by over a million times (source: cms.gov).

On the other hand, the relative cost of healthcare has grown much more modestly. A tonsillectomy in 1848 cost $10.00 which is equivalent to $5,020 in today’s dollars using relative share per capita GDP (source: Relative Share). Generally speaking, a modern tonsillectomy costs $5,442 (source: health.costhelper.com), an increase of around 10%. One is left to conclude that people spend a great more on healthcare today, not because of the item cost of the products, but rather, the sheer number of products people can or feel they must purchase.

So why is this important? It is important because the goal of “affordable healthcare” will have less to do with cheaper MRI visits or drug costs and much more to do with limitations on products and procedures available to the public. And since technology keeps exploding the possible number of products and procedures and shows no inclination to slow down, control of healthcare costs will demand either voluntary or mandated restraint on what people have access too.

In the 1980’s, the Soviet Union was filled with supermarkets — empty supermarkets. They were empty not because bread was too expensive; the supermarkets were empty because the government was forced to ration supply to control the demand. Given the compound problem of no incentives to increase production and no disincentive to purchase items that were subsidized by the State, forced rationing was the consequence. That is, the lack of a free market crushed the idea that socialism could provide a “free lunch” to its citizens without dictating what and when the comrades got to eat.

Government provided healthcare, or a single-payer system as it is sometimes euphemistically referred, is impossible for the same reasons. Consumer demand MUST be controlled in any system with virtually limitless choices. The only outcome of liberal visions for universal healthcare is a landscape of gray hospital buildings without doctors, drugs, or equipment and a bureaucrat gatekeeper checking your ration card, and proclaiming: “sorry comrade, you already had a broken arm this year.”

I met a young man the other day, let’s call him “Henry.” Henry had just come home from the hospital where he underwent bariatric surgery to reduce the size of his stomach. The procedure itself cost over $12,000, and the total cost of the entire process exceeded $25,000 all of which was covered by his insurance. While many people might consider bariatric surgery (e.g. gastric bypass) an elective or even cosmetic surgery, not Henry. He’s just divorced and back in the dating pool, but it wasn’t his appearance that troubled Henry, he was desperately concerned about the possibility that his overweight condition might cause him to become diabetic or even succumb to heart disease.

Since Henry’s insurance would not pay for elective surgery, the solution was simple. His doctor just recorded the diagnosis as “Early Onset Diabetes Mellitus”, and magically the insurance company forked over the $25k. Henry is not a bad man, not in the cosmic sense. It’s just easier for Henry to defraud the insurance industry than to put down his fork. Henry is venal. He is awash in a system that is just chock full of product and procedures. He’s a consumer and Henry has a catalog of unbelievable variety in front of him.

It is true, that my father would have looked at Henry as if he were a burglar who had just crept into his house and stolen his paycheck. In 1930, there was no global feeling of entitlement, there was no cornucopia of products, and there was no expectation that your neighbor had a responsibility to help you pay for whatever you wanted. In 1930, you expected to pay for what you received, whether it was a loaf of bread, or a new car, or a cast for your broken leg. But that was 1930 — not 2017. Today, Henry’s action is simply seen as normal behavior without judgment. Henry probably does not even consider the fact that his trimmer body was paid for by his fellow citizens.

So then, here we have the Paradox of Healthcare: a free healthcare system that results in the most expensive kind of healthcare even though specific products and procedures get cheaper.

In the last hundred years, we have gone from a handful of medical options to millions. In the next 50 years, the catalog of medical options will grow to billions. The cost of healthcare is driven primarily by the number of options we choose NOT simply the cost of each option. For example, in 1900 an individual might visit a doctor or buy a medication once a year, in 2017 individuals probably see a doctor, get an x-ray, or buy a prescription medication 10 to 20 times more often.

In 2017, Americans spent over $10,000 per person on average on health care related products and services (source: World Bank Group). That amounts to between $500 and $1000 per item in 2017. In 1900, an individual might make one expenditure of $25 to $50. Accounting for inflation, $25 to $50 in 1900 equals $500 to $1000 in 2017. In other words, the ITEM price for a medical product or service has remained relatively the same — it is the NUMBER of purchases that has increased the per capita cost, not the cost of a single purchase.

So, while lowering the cost of drugs and procedures is important, only a reduction in the number of purchases can make healthcare more affordable. Preventative care can reduce the number of required purchases, good lifestyle choices can reduce the number of required purchases, predictive DNA analysis and effective epidemiology can reduce purchases, but such actions will only lower per capita expenses slightly. All of these actions taken together might affect the total by a few percent, they cannot make a dent in the ever-growing number of possible choices that truly determine the per capita expenditures.

Only some form of restraint can limit the number of choices and therefore the total cost. The question is: what form of restraint do you want? There really are only two kinds of restraint, forced and voluntary.

The capitalist free market is a harsh taskmaster, it demands individual responsibility, hard work, and the expectation that rewards based on meritorious action expand choice — but the free market is VOLUNTARY. The alternative is the great lie of the democrat and socialist liberal elite. The alternative to the free market is the jackboot of rationing and control, and its name is the “single-payer system.”

What your liberal friend will not tell you is pretty simple. Ultimately, if healthcare is provided by a central authority it is doomed for failure and bankruptcy, unless that central authority also tells you what healthcare you are permitted to have, what life style the government determines is best for you, and what rules you must adhere to in order to receive the government’s largess.

In other words — surrender your freedom and we’ll keep you alive.